Why you should visit Sabang, Aceh

- October 18, 2018

- Discover

Located on the enchanting island of Sabang, Aceh, Casa Nemo Beach Resort & Spa stands as a gem beckoning travellers seeking an... Read More

What do we know about a traditional Aceh house?

The traditional Aceh house has been discussed at length by anthropologist and architect historian of various period, among others, Snouck Hurgronje, James Siegel, Roxane Waterson, Greg Dall, and Peter Nas.[1] Each of them focus on specific dimension of the traditional Aceh house, but the common themes that recur is, although space is gendered in the dwelling house, it is by no means function as a hierarchical system. Women, whose domain belong to the back of the house, are instead, the owner of the house which is reflected quite literally in the local idiom of a wife: nyang po rumoh.

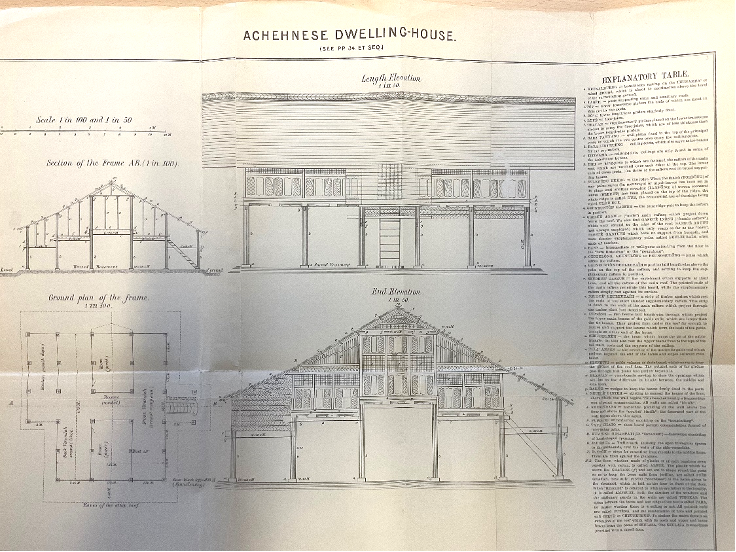

The traditional Aceh house from The Achehnese Volume I by Snouck Hurgronje As many other traditional houses of the Malay Archipelago, the traditional Aceh house is built above the ground, with the support of wooden pillars, varies from 16, 20, or 40 at its largest. In his ethnographical work, Hurgronje noted that the Aceh traditional house can be classified as a movable property because it is not attached to the ground, and it can easily be

dismantled and reassembled elsewhere. Such vernacular architecture construction corresponds to the ecological setting of Aceh, where flooding and earthquakes occurred frequently and to prevent its dwellers from wild animals such as tiger or snakes. The orientation of house is usually following the east-west axis, aligned with the direction of qibla for the purpose of Islamic daily prayer. The main entrance is placed on the front, with stairways of odd numbers, and the back entrance is limited for private use, also with odd numbers of steps. Horizontally, the house can be divided into three compartments: the front veranda (rumoh rinyeun), the central passage (rambat) connecting rooms of parents and children, and the rear veranda (rumoh likot).[2]

Understanding local custom, cosmology, and gender dimensions through traditional Aceh house

The front veranda belongs to the male inhabitants, where guest is welcome, public events and prayer are being held. The back veranda is the domain of female inhabitants, where kitchen is located, and childrearing activities are performed. Vertically, the house can be seen as a unity of three cosmographical layers: the attic where heirlooms is storage, represents the sacred upper world, where ancestors and Gods belong, the middle space of human, where everyday life took place, and the beneath of house, considered as the profane, where non-human beings, including animals and spirit, settled.[3]

Regarding the gendered spatial arrangement as mentioned earlier, Roxana Waterson wrote that, although the domains of women and men are placed in such an opposite direction, it should not be perceived as the inferiority of women to men. Waterson offered a different perspective that is to look on the spatial layout from the centre passage and the parents’ room as the inner, meanwhile the back and front veranda as the outer. It can reflect what Waterson stated as, “expression of a relation between affines.”[4] Another note on this matter, more broadly to the realm of authority inside the house, is addressed by both James Siegel and Snouck Hurgronje. The two of them noted that the presence of man inside the house should be understood as a guest, who is not allowed to intervene on domestic issues. Such relationship emerges from the status of house ownership, along with other resources like rice-field that falls on the women behalf.

How traditional Aceh house affected everyday gender relationship? In the traditional custom in Aceh, once woman enter marriage, her parents will present a rice-field and a house, which she can retain a full ownership once a child is born or depends on the agreement.[5] A small ceremony known as “geumeukleh” to signify the full possession of house is held by the parents, and they will build a new house for themselves, until the next daughter marries the same practice of house giving will occur. This practice thus give rise to the independency of woman and the dependency of man to his wife, given that man does not own property and rice-field or inherit it from their parents, unless they do not have sisters. If his wife owns a rice-field, man is expected to do half the work, but as argued by Siegel, “because the rice cultivation system in Aceh is not very intensive, only a handful of men needed in each village to cultivate the fields.”[6] The remaining men, especially who have been married, leave to other region in order to make earnings outside of his wife properties, thus fulfil his role as a husband.

The position of man and woman inside the house thus implicate how their presence is situated in a broader spatial setting.As discussed earlier, due to the ownership of house to women, a gampong usually constitute houses belongs to women members, sisters or aunts, from one extended family.[7] During his period of research, Hurgronje observed that most gampong has a fence, fields (blang) and garden (lampoh), as well as a building with similar construction to traditional house, but without wall, passage, or window.[8] This building is meunasah, a public hall, like a chapel, but used by men discuss village affairs, praying during fasting month, and a place to sleep for unmarried men and adolescent boys.[9] Prior to the age of maturity, boys lived in their mother house and to gain manhood, one will go through what Siegel termed as “a progessive removal from the household,” which is aligned with coming-of-age phase in Islam.[10] The removal started at the age of six, when boys learn to recite the Holy Koran and spend less time at home. Once they got circumcised, around the age of eight and reach puberty, boys are obliged to perform the daily prayers in mosque or meunasah, thus put them away from their mother’s house. Adolescent boys only come to their mother house to eat or do their part in a rice-field own by their mother, and by night, they will return to meunasah to sleep. In his footnotes about this “nocturnal separation,” Hurgronje wrote that such practice is absence among the Malays across the strait, although the meunasah is present, but its main usage is for religious activities.

[1] See Dall, Greg. 1982. “The traditional Acehnese house”. The Malay-Islamic World of Sumatra : Studies in Polities and Culture. 35-61.; Iwabuchi, Akifumi, and Peter J.M. Nas. n.d. “Aceh, Gayo and Alas: Traditional house forms in the Special Region of Aceh”. 17-47.; Waterson, Roxana. 1990. The living house: an anthropology of architecture in South-East Asia. Singapore: University of Oxford Press.

[2] Hurgronje, The Achehnese Volume I, pp.35.

[3] Waterson, Roxana. 1990. The living house: an anthropology of architecture in South-East Asia. Singapore: University of Oxford Press.p.93.

[4] Ibid.184.

[5] Siegel, James T. The Rope of God. 2000. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.139

[6] Ibid.53

[7] Ibid. p. 52.

[8] Hurgronje, Snouck. The Acehnese Volume , p. 59.

[9] Siegel, James T. The Rope of God, p. 52

[10] Ibid., pp.150-152.